This post examines the various replication strategies used by popular time-series and OLAP databases to implement high-availability. Our learnings from this research have inspired us as we continue to build replication into our own performance-focused database, QuestDB. The database is built in C++, low latency Java, and recently Rust! The codebase has no external dependencies and we implement SQL with native time-series extensions.

After being unable to ride my new electric bike to work yet again because it was in the shop (this time because of a wiring problem that prevented the bike from running!), I started to think about how I could create some redundancy in my biking setup so I wouldn't be stuck riding the Tube for weeks at a time due to simple maintenance or a supply chain issue. What if I had another bike to ride while my current one is being fixed? That would definitely help, but electric bikes are expensive, and there's little room to store a backup bike in my cozy London apartment.

Believe it or not, this problem is similar to what I've been tackling at my day job as a database developer. Just like bicycles, databases can break down too! Sometimes hardware fails mysteriously, or a network config has changed and your database is no longer reachable. Sure, you could always restore your data from a backup onto new hardware in the event of a failure, but then you're stuck with downtime and potentially lost data; and that's assuming you've tested your restore process recently to ensure that it even works! Even if you're able to run a restore seamlessly, just like I need to wait for the shop to finish fixing my bike before I can start riding it to work again, you would also need to wait for the restore to complete and the new database to be configured before using it.

But luckily, unlike my bike situation, modern databases have the capability to stay online and continue their normal operations when things go wrong. This is especially important in the world of time series databases, which are designed to be constantly writing data, in many cases almost nonstop. There's no time to restore from a backup, since precious data could be lost during any period of downtime.

How can this happen? The answer is through replication! By synchronizing multiple database nodes and building a solution for moving execution over to healthy ones when a node breaks down (write failover), databases can ensure that no data is lost. This is like if I got a flat tire on my commute and could switch to a spare bike right on the spot in the middle of the road! Seems pretty cool, right?

As we start our journey towards making QuestDB distributed, we take the time to analyze how several popular time-series/OLAP databases implement high availability to highlight the pros and cons of each approach. Along with a review of the fundamentals, we also share QuestDB's own approach and our plans for the future.

Failover

Let's take a look at a scenario is when an application writes to a database, but it suddenly gets a network disconnect. What should happen in this case?

The application should switch to a replicated node and continue inserting data.

For example, if I had an application App writing to DB Node 1 with replica

DB Node 2 I could draw this scenario as a sequence diagram:

Seems straightforward, but is it easy to get a database to play its part in this

dance? I believe it's not. To achieve this, the database has to be able to write

data into the same table A through multiple nodes. In the general case, the

database also has to evolve the schema to support adding/removing columns from

multiple nodes and applying the transaction in exactly the same order on all the

replicas. This is because some transactions like INSERT and UPDATE that are

executed on the same row will have different outcomes if applied in the wrong

order.

To summarize, a database needs to be able to:

-

Write data to the same table using multiple DB Nodes (multi-master replication) or mirror the data to a read-only replicated node with automatic failover

-

Evolve table schemas such that the same table columns can be added simultaneously from multiple connections

-

Maintain the global order of the writes and schema changes across replica nodes

Sync and Async replication

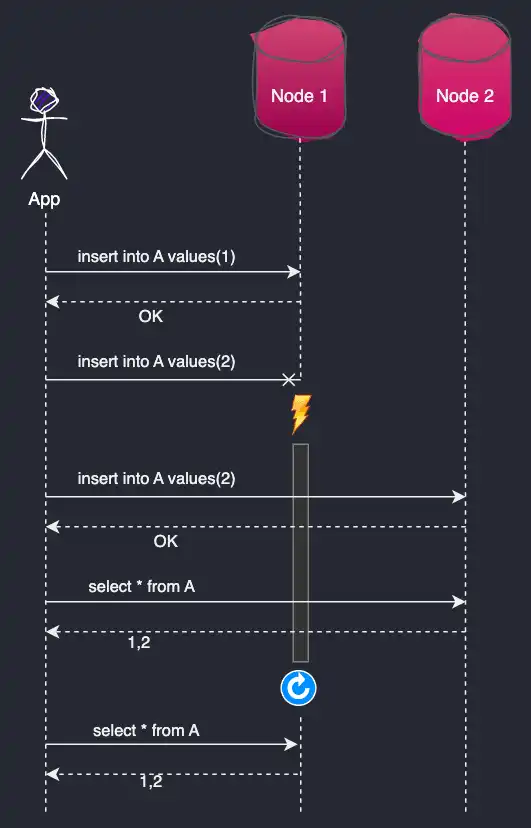

Different things can go wrong with databases when a failure happens. For

instance, there can be two reasons why the database Node 1 may not reply to

the second insert, insert into A values(2): it can either be that the node

fails to receive and process the transaction, or that the data is inserted but

the OK reply is not delivered back to the application due to a network

disconnect.

To avoid losing the second insert after disconnecting from Node 1, the

application has to repeat transaction insert into A values(2) to Node 2. The

application also has to do the repeated insert into A values(2) attempt in

such a way that the database does not create a duplicate row in the case when

the same insert has already been processed by Node 1 but an OK reply is not

delivered back to the application. In order to achieve these goals, all data

inserted into Node 1 has to be readable from Node 2 immediately for the

application to perform the deduplication on failures. Alternatively, there must

be another built-in mechanism to de-duplicate the inserted data in the database.

This leads to the conclusion that at least one of the points below has to exist

for no-gap, no-duplicate write failover:

-

Data written to one node is immediately selectable through all other replicas so that the writing application can check for the duplicates

-

There is a de-duplication mechanism built into the insert protocol or table storage

The first bullet point above is also called Synchronous (Sync) Replication where

Node 1 replies OK only after an insert is already replicated to Node 2. In

contrast, Asynchronous (Async) replication allows Node 1 to reply OK to the

App before replicating the inserted data to Node 2. This way Node 2 may

not receive the first insert before Node 1 goes down, so the database will

have to reattempt to replicate the data when Node 1 is started or connected

back.

Choice of replication flavor

Back to my bike analogy, a database configured in single primary with a read-only replica in Sync mode is something akin to riding one bike while simultaneously trying to roll another alongside you at all times. You can imagine that it's pretty hard to ride while simultaneously balancing on two bikes, and that it's nearly impossible to actually cycle quickly!

On the other hand, a database configured in single primary with a read-only Async replica is similar to me buying a spare bike, storing it at work, and synchronizing my trip data when the bikes are at the same place. In case of a breakdown, I'll lose data from that particular journey but I would still be able to continue commuting on the spare bike the same day.

I imagine that multi-master replication is something like riding with a friend on two tandem bikes, where everyone is riding the tandem on the first seat. If one of the tandems breaks, the rider can move to the back seat of the other one. Multi-master Sync replication is riding two tandems next to each other without the freedom of turning or stopping independently. Async replication would be the independent rides with occasional location/trip data catch-ups.

Async replication is the most reasonable choice in the world of bicycles; I do not see people running bikes in sync on the streets. It is also a default/only choice for many in the database world. Sync replication can be simple to reason about, and may look like the best solution overall, but it has a hefty performance price to pay since each step needs to wait until it is completed on every node. Counterintuitively, even though synchronous replication makes data available to multiple nodes at the same time, it also results in lower availability of the cluster since it dramatically reduces the transactions rate.

There is no silver bullet for the write failover problem and every database offers different replication flavors to choose from. To find the best option for QuestDB, we did serious research on how replication in other time-series databases handles the write failover and here are some of the results.

TimescaleDB

Everyone loves classic relational databases, and nearly every developer is prepared to answer interview questions about ACID properties and sometimes even about Transaction Isolation levels of different RDMS systems (and what can go wrong with each of them!). Building distributed Read / Write applications using a RDBMS is not easy but it is definitely doable.

PostgreSQL is one of the leading open source RDBMSes, and many say that it's more than just a database. Postgres is also an extensible platform where you can, for example, add a geographical location column type, a geospatial SQL Query syntax, and indexes, effectively turning it into GIS system. Similarly, TimescaleDB is a PostgreSQL extension built to optimize the storage and query performance of time-series workloads.

Out of the box, TimescaleDB inherits its replication functionality from Postgres. PostgreSQL supports multiple read-only replicas with Sync or Async replication with all the ACID and Transaction Isolation properties, and so does Timescale.

Unfortunately, automatic failover is solved neither by PostgreSQL nor TimescaleDB, but there are 3rd-party solutions like Patroni that add support for that functionality. PostgreSQL describes the process of failover as STONITH (Shoot The Other Node In The Head), meaning that the primary node has to be shot down once it starts to misbehave.

Running Sync replication can solve the data gaps and duplicate problems after

the failover. If the application detects the failover, it can re-run the last

non-confirmed INSERT as an UPSERT.

With Async replication, a few recent transactions may be missing on the replica

that is promoted to primary. This is because the old primary node had to be shot

down (STONISHed) and there is no trivial way to move the missing data from that

"dead" node to the new primary node post-failover.

ClickHouse

ClickHouse had been developed open source for many years by Yandex, a search provider in Russia. ClickHouse's functionality in open source (Apache 2.0) is comprehensive and includes high availability and horizontal scaling. There are also quite a few independent managed cloud offerings that support ClickHouse:

It makes sense to talk about ClickHouse's replication in the context of its Open Source product, since cloud features can vary dramatically from provider to provider.

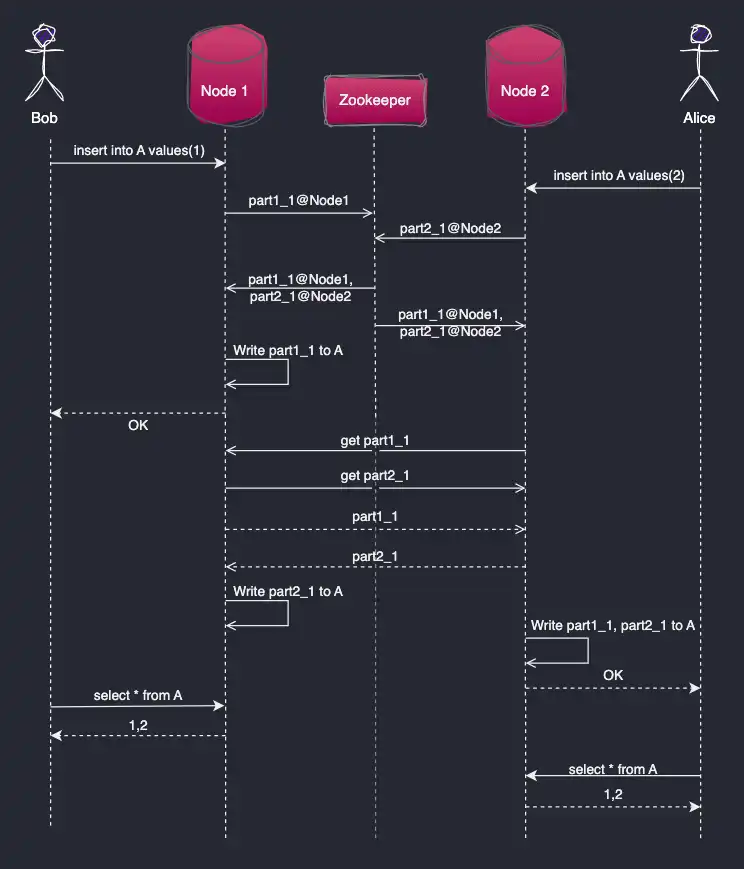

The great thing about ClickHouse open source is that it supports multi-master

replication. So if one creates a cluster with 2 nodes (Node 1 and Node 2)

and replicated table A (using the ReplicationMergeTree engine):

When Bob sends to Node 1

INSERT INTO A VALUES(1);

And Alice sends to Node 2

INSERT INTO A VALUES(2);

Both records will be written to each of the nodes. When the

INSERT INTO A VALUES(1) statement is received on Node 1, ClickHouse writes

it to part 1_1. Next, Node 1 registers the data part with the Zookeeper (or

ClickHouse Keeper). Zookeeper notifies each node about the new part, and the

nodes download the data from the source and apply it to the local table replica.

The same process happens simultaneously with INSERT 2.

In this architecture, inserts can be written to each of the nodes in parallel.

What about reading the data back? ClickHouse documentation states that the

replication process is Asynchronous and it may take some time for Node 2 to

catch up with Node 1. There is however an option to specify insert_quorum

with every insert. If the insert_quorum is set to 2 then the application

gets confirmation back from the database after both Node 1 and Node 2 have

inserted the data, effectively turning this into Sync replication. There are a

few more settings to consider like insert_quorum_parallel,

insert_quorum_timeout, and select_sequential_consistency to define how

concurrent parallel inserts work.

It is also possible to modify the table schema by adding new columns on the

replicated table. An ALTER TABLE statement can be sent to any of the nodes in

the cluster, and it will be replicated across the nodes. ClickHouse does not

allow concurrent table schema change execution so if 2 of the nodes receive the

same non-conflicting statement:

ALTER table A add column if not exists TIMESTAMP datatime64(6)

one of the nodes can reply with the failure:

Metadata on replica is not up to date with common metadata in Zookeeper.

It means that this replica still not applied some of previous alters.

Probably too many alters executing concurrently (highly not recommended).

You can retry this error

SQL Update statements are also written in ClickHouse dialect as ALTER TABLE

but fortunately, they can be executed in parallel without the above error.

ClickHouse also has a useful method to solve lost write confirmations; in cases

where an INSERT (or other) query confirmation is lost because of a network

disconnect or timeout, the client can resend the whole block of data in exactly

the same way to any other available node. The receiving node then calculates the

hash code of the data and not apply it a second time if it is able to recognize

that this data has already been applied via another node.

There are more options and flavors of how to set up replication in ClickHouse,

the most popular approach being ReplicatedMergeTree storage.

InfluxDB

InfluxDB has the highest DB engines time series ranking at the time of writing, and I feel that it has to be included here even though InfluxData removed the clustering product from the open source version in 2016 to sell it as a commercial product, InfluxDB Enterprise. Since then, their focus has shifted from the enterprise version to the cloud offering in recent years, where they have built InfluxDB Cloud v2. While this is a closed-source system, its high-level architecture is deducible from the marketing diagrams InfluxData officially provides.

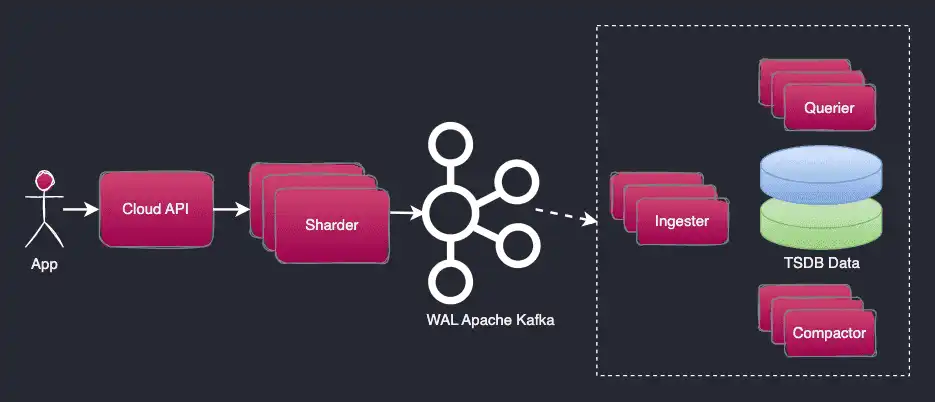

InfluxDB Cloud v2 persists incoming writes to the Write Ahead Log (WAL) written over a Kafka cluster. It is a clean solution that solves the durability and distribution of the WAL and ensures that the data is already replicated when the client receives a write confirmation.

WAL application to "Queriable" table storage runs asynchronously in the Ingester component, consuming messages from Kafka and writing them to 2 independent TSDB copies. There is a delay between reading the message confirmed to be written, in Influx terms this is called Time to Become Readable.

Influx protocol messages are idempotent in the sense that the same message can be processed many times without creating duplicates. This is because in InfluxDB, the same set of tags can have only one row per timestamp value. So if one sends a line:

measurement1 field=34.23 1562387656300000000

and then sends another line with the same measurement and timestamp:

measurement1 new_fields=0.1234 1562387656300000000

the new field value will be added to the same line as if the fields were sent together, in the same message:

measurement1 field=34.23,new_fields=0.1234 1562387656300000000

And if any of the above messages are sent again, Influx will not add a new row. This approach solves the problem of resending data on timeout or lost replies. So if the client does not receive a write confirmation from Influx cloud, it can re-send the same data again and again. When the data is sent with the same timestamp and tag set from different connections:

measurement1 field1=1 1677851990000000000

measurement1 field1=2,field2=2000 1677851990000000000

The querying storage nodes can become inconsistent for some time, returning any row out of the 3:

| field1 | field2 | time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2023-03-03T13:59:50.000Z | |

| 2 | 2000 | 2023-03-03T13:59:50.000Z |

| 1 | 2000 | 2023-03-03T13:59:50.000Z |

It can even be that the first query returns field1=1, a second query returns

field1=2 and then a third tries flipping back to field1=1. Eventually, the

query result will become stable and return the same data on each run. This is a

very typical outcome for querying nodes in Round Robin with Async replication.

The Influx data model also solves the problem of a dynamically evolving schema. Since there are no traditional columns (since any unknown fields and tags that are encountered are added automatically by the database engine), there is no problem writing a different set of fields for the same measurement by design. Influx also checks for schema conflicts and returns errors to the writing application if there are any. For example, if the same field is sent as a number and then as a string:

m1 value=34.23 1562387656300000000

m1 value="hello" 1562387656300000123

The write will fail with the error

column value is type f64 but write has type string or

column value is type string but write has type f64.

Summary

Here is the summary of the replication features supported by time-series databases relevant to High Availability write use case:

| PostgreSQL / TimescaleDB | ClickHouse | InfluxDB Cloud | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-master replication | No | Yes | No |

| Supports Sync replication | Yes | Yes | No |

| Supports Async replication | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Concurrently evolves replicated table schema | Yes | Yes¹ | Yes² |

| Same Insert / Update order on all nodes | Yes | Yes | Yes² |

| No gaps and duplicates after failover | Sync mode only | Yes | Yes |

| Uses WAL for Replication | Yes | Yes³ | Yes |

¹ Concurrent schema updates have to be re-tried

² InfluxDB cloud is a closed-source system, certain conclusions are made on the assumption of the reasonable use of Kafka WAL partitioning and the correctness of this claim depends on the implementation.

³ ClickHouse replication Data Part plays the role of WAL

To draw up some conclusions:

-

All 3 systems replicate by writing to the Write Ahead Log and copying it across the nodes.

-

Asynchronous replication, where data written to Node 1 is eventually visible at Node 2, is the most popular approach used by InfluxDB Cloud and is the default in both ClickHouse and Postgres.

-

Postgres / Timescale replication can be used in both synchronous and asynchronous modes, but it does not have multi-master replication and there is no option for automatic failover. It is not possible to solve write failover without additional software systems or human intervention.

-

Multi-master replication is available in ClickHouse. There are also enough available settings to strike an appropriate balance between experiencing data loss (in extreme scenarios) and writing throughput.

-

InfluxDB does not offer replication support in its open source product. There is a closed-source cloud solution that leverages Kafka to solve automatic write failover. Kafka replication is not multi-master but with the help of automatic failover, it solves high-availability write use cases.

QuestDB Replication Plans

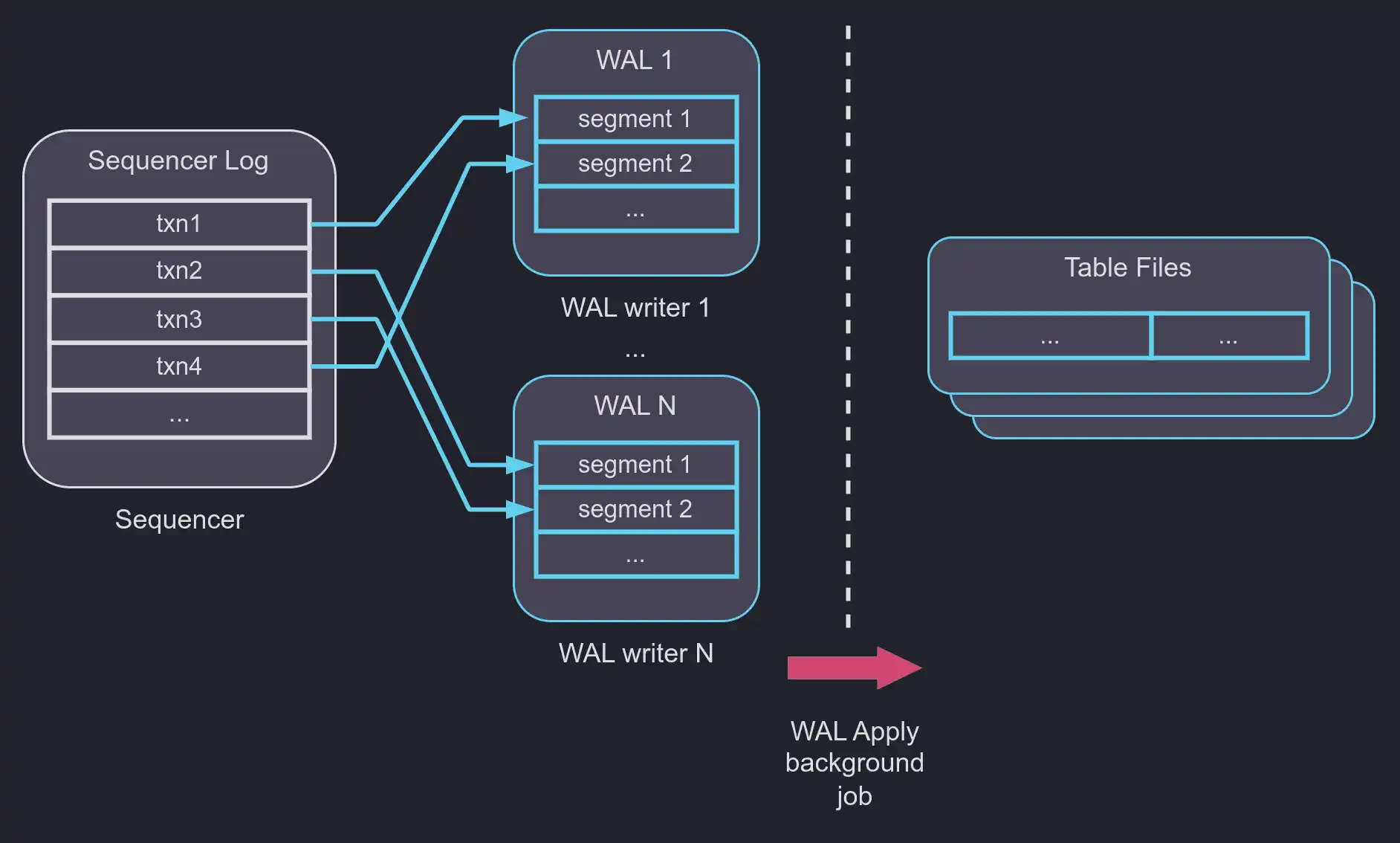

QuestDB released Write Ahead Log table storage mode in v7.0 as the first step in our replication journey. It uses a multi-master write architecture internally to make non-locking writes to the same table possible from parallel connections. Transactions are written in parallel to different WAL segments, and a global order of commits is maintained in a Sequencer component. The most complicated bit is automatic schema conflict resolution so that table schema changes can also be be performed in parallel.

We tried to avoid having a Write Ahead Log for a long time, writing directly into the table storage. It was not an easy decision to accept WAL write amplification for the sake of a cleaner path to replication and non-locking parallel writes. In the end, the additional write operations did not impact overall throughput. On the contrary, because of better parallelism, we achieved 3x better write performance in Time Series Benchmarking Suite compared to our own (quite extraordinary) performance for non-WAL tables.

Looking at how other databases solve the replication problem, we chose our goal to be achieving multi-master replication with Async consistency. We believe that this approach strikes the best balance of fault tolerance and transaction throughput. And it is essential to have a built-in write de-duplication mechanism for automatic write failover cases. The next steps for QuestDB will be to move the built-in Sequencer component to a distributed environment and solve WAL sharing between multiple instances.

Riding tandem bicycles with a friend is the best redundancy solution we see for QuestDB. And as for my commute problem, well, I still don't know how to solve it. You are more than welcome to join our Slack Community and share your feedback. You can also play with QuestDB live demo or play.questdb.io to see how fast it rides. And, of course, open-source contributions to our project on GitHub are more than welcome.