EXPLAIN Your SQL Query Plan

We recently implemented the EXPLAIN SQL

keyword. In this new series of articles, we are going to shed light on how to

fine tune your SQL queries to improve performance, with the help of EXPLAIN.

We start the first post of this series with an introduction to the EXPLAIN

execution plan.

Optimization in SQL

One of the first tasks I got when I started working as a Java software developer was about optimization: optimization for nightly processes of an online reservation system, a traditional three-tiered Java web application backed by then-popular RDBMS. A story like many others - processes that started fast and nimble became slow and resource-hungry over the years, up to a point where they were running late, overlapped with daily load, or just errored out.

Not good.

Quick code reconnaissance showed that the said batch processes relied heavily on the database. They ran many custom multi-page-long SQLs one after another and exported some results to data files. Checking logs revealed that some took seconds while others dragged on for tens of minutes. Profiling JVM only showed that the application is waiting on queries. System logs weren't more useful than that - they showed lots of IO and CPU load but didn't give any hint as to why.

It seems the only option is to speed up queries.

Right, but how?

At first, I had no idea. I simply took the slowest query and started making changes here and there. Most changes didn't improve the query speed, and when they did, it turned out that the query was broken. Applying good advice from Internet forums didn't help at all. After a few hours, I gave up and tried asking local database gurus for help. To my surprise, the suggestions I received were repeating the 'Internet wisdom', e.g.:

- "Use hint X."

- "

UNIONis slow, rewrite it toUNION ALL." - "You have to use index, because full table scan is slow."

While still trying to apply any advice I could find and feeling tired, I

discovered a thick tome on the company's IT bookshelf - an RDBMS textbook.

That's where I found the right tool for the job - the EXPLAIN command.

The basics of a SQL database

Initially, EXPLAIN seemed like some black art - hard to follow and full of

arcane terms. Before it really clicked with me, I had to go through the book and

learn some fundamental concepts. That's why, before going any further, let's

focus on basic stuff for a moment.

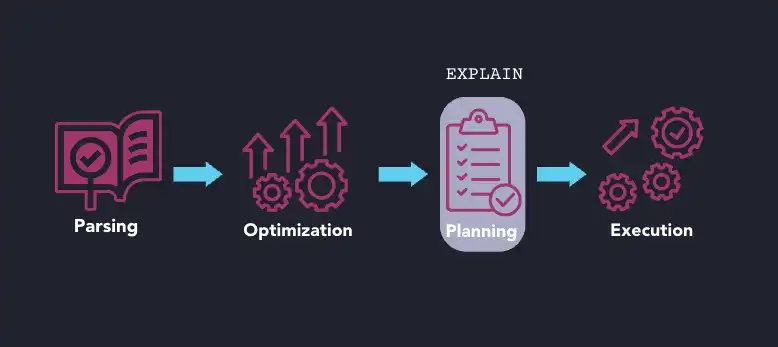

QuestDB processes queries in the following phases :

- Parsing - Query text is parsed and a model is created.

- Optimization - The query is rewritten for the best performance.

- Planning - An execution plan is created, and the best table scan and join methods are chosen.

- Execution - Tables are accessed according to the execution plan and outcomes are produced.

SQL is just the query interface and the database must decide on a great many things before it can produce results. These things include:

- How to access a table - e.g. full or index scan, scan forward or backward.

- How to join tables - e.g. nested loop, merge, or hash join.

- How to order joins - e.g. 5 tables can be joined in 5! = 120 different orders.

- How to optimize expressions - e.g. evaluate constant expression once instead of for every row.

The above is just the tip of the iceberg, a lot is happening under the hood and many factors influence the end performance of a query.

EXPLAIN SQL keyword explained

The EXPLAIN SQL keyword shows

the execution plan (the outcome of step 3. above), which is the logical

algorithm used to implement a given statement and thus 'explains' its

performance. Even though it's not part of the SQL standard, many databases, such

as PostgreSQL, MySQL, and Oracle, do implement their own variant of EXPLAIN.

Contrary to SQL, which is a high-level declarative language, EXPLAIN uses

terms that are often low-level, and related to the database implementation, for

example, hash joins or index scan. Learning the fundamental QuestDB

concepts is essential to fully understand how queries work

and how to improve their performance.

Thanks to this type of tool, I was able to first, understand what happens under the hood when a query is run, and why it happens. Furthermore, I was able to reduce the nightly process run time well beyond what was expected.

First example of EXPLAIN in SQL

Now, it's time for practice. Let's have a look at the following queries that use

the trades table in the QuestDB demo instance:

CREATE TABLE trades (symbol SYMBOL CAPACITY 256 CACHE,side SYMBOL CAPACITY 256 CACHE,price DOUBLE,amount DOUBLE,timestamp TIMESTAMP) TIMESTAMP (timestamp) PARTITION BY DAY;

Query A:

SELECT count(*) FROM trades WHERE price = 0.0f;

Query B:

SELECT count(*) FROM trades WHERE price = 0.0;

For hot data, response times are :

- Query A: 160ms

- Query B: 50ms

Can you guess why?

It could be a number of things, but why guess when you can check:

EXPLAIN SELECT count(*) FROM trades WHERE price = 0.0f;

| QUERY PLAN |

|---|

| Count (4) |

| Async Filter (3) |

| filter: price=0.0f |

| DataFrame |

| Row forward scan (2) |

| Frame forward scan on: trades (1) |

The output is a tree of nodes - stages in query processing - that have properties and/or subnodes (aka child nodes).

In the plan above we have the following nodes and properties:

- nodes - They start with an upper-case letter and have bigger indents than

properties:

CountAsync FilterDataFrameRow forward scanFrame forward scan

- properties:

price=0.0fon: trades

According to the plan, the query contains the following steps:

- Forward scan all the partitions of the table.

- Forward scan all rows in each partition.

- Apply filters to each row.

- Count all rows that pass it.

Next, we check the plan for query B:

EXPLAIN SELECT count(*) FROM trades WHERE price = 0.0;

| QUERY PLAN |

|---|

| Count |

| Async JIT Filter |

| filter: price=0.0d |

| DataFrame |

| Row forward scan |

| Frame forward scan on: trades |

Can you spot the difference?

It's about the JIT.

The second query is faster because it uses Just-In-Time-compiled filter!

The first query doesn't use it due to column and argument type mismatch.

In both cases, the trades table is fully scanned, which is reflected by

DataFrame and the child nodes.

The QuestDB Web Console limits the number of output rows to 1k, so it is not the best way to measure the performance of queries that return data sets bigger than the limit.

Second example of EXPLAIN in SQL

Let's look at the pos, another table available

in the QuestDB demo instance:

CREATE TABLE pos (time TIMESTAMP,id SYMBOL CAPACITY 256 CACHE INDEX CAPACITY 512,lat DOUBLE,lon DOUBLE,geo6 GEOHASH(6c),geo12 GEOHASH(12c)) TIMESTAMP (time) PARTITION BY DAY;

What if we need to count the number of records with a given id prefix?

SELECT count(*)FROM posWHERE substring(id,1,21) = 'NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKP'

The result is 678 and it takes about 1.2s.

A bit slow for just a few hundred records.

Let's used EXPLAIN on the query and inspect the plan:

| QUERY PLAN |

|---|

| Count (1) |

| Async Filter (2) |

| filter: substring(id,1,21)='NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPS' |

| workers: 14 |

| DataFrame (3) |

| Row forward scan (3) |

| Frame forward scan on: pos (3) |

I have annotated the plan with some numbers to illustrate the information. From the table, we can see that query counts (1 in the table) records filtered by an asynchronous, multi-threaded filter (marked as 2), which scans the whole table (marked as 3).

Considering the number of records (678 rows in the result vs 120M in the whole

table) it seems strange that the index on id wasn't used.

What can we do here?

In many databases, index access requires a query predicate to match the expression used in the index definition.

If a mismatch is detected, the index would need to be fully scanned, which is much more costly than a single value or value range lookup.

In this case, we have a symbol column, so assuming that id contains A-Z

letters only and is 22-characters long, we can rewrite the expression with a

IN clause:

SELECT count(*)FROM posWHERE id IN ('NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPA','NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPB' ... 'NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPZ');

In effect, the response time shrinks to 3ms, about 400 times less.

Let's check out why:

EXPLAIN SELECT count(*)FROM posWHERE id IN ('NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPA','NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPB' ... 'NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPZ');

| QUERY PLAN |

|---|

| Count |

| FilterOnValues |

| Cursor-order scan |

| Index forward scan on: id deferred: true |

| filter: id='NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPA' |

| ... |

| Index forward scan on: id deferred: true |

| filter: id='NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPZ' |

| Frame forward scan on: pos |

This time, instead of fully scanning the table, QuestDB decides to scan the index :

-

First, it finds id='NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPA' key.

-

The engine iterates over the list of associated row ids and accesses the

postable. -

It locates the 'NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPB' key, etc.

If we had to query by one complete value, like this one:

SELECT count(*)FROM posWHERE id IN ('NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPS')

The plan would be even simpler and more effective:

| QUERY PLAN |

|---|

| Count |

| DeferredSingleSymbolFilterDataFrame |

| Index forward scan on: id deferred: true |

| filter: id='NSTTQFPKISYEGDLPJFEKPS' |

| Frame forward scan on: pos |

It returns results in about 0.5 ms.

The rule-based optimizer used in QuestDB considers index access only for simple symbol_column = constant | function() expressions.

Let's get back to the trades table. Say we'd like to count the number of

trades in the last 24 hours :

SELECT count(*)FROM tradesWHERE timestamp > dateadd('d', -1 ,systimestamp());

It works fine but why does it take a second?

Let's see :

EXPLAIN SELECT count(*)FROM tradesWHERE timestamp > dateadd('d', -1 ,systimestamp());

Plan:

| QUERY PLAN |

|---|

| Count |

| Async Filter |

| filter: dateadd('d',-1,systimestamp())<timestamp |

| workers: 14 |

| DataFrame |

| Row forward scan |

| Frame forward scan on: trades |

Weird! The query is doing a full scan and filters out all records older than a day.

The timestamp column is a designated timestamp, so what could be the reason?

Let's try to rephrase it a bit using timestamp literal:

SELECT count(*)FROM tradesWHERE timestamp > '2023-01-16T09:51:43.000000Z'

This time result arrives in 1 millisecond.

What's going on?

EXPLAIN shows:

| QUERY PLAN |

|---|

| Count |

| DataFrame |

| Row forward scan |

| Interval forward scan on: trades |

| intervals: [static=[1673862703000001,9223372036854775807] |

Instead of a full scan, we've only an interval scan limited to ['2023-01-16T09:51:43.000000Z', max timestamp] time range.

Now, we've got the right plan but don't know the reason why the database chooses

it over the former one. To understand the difference we need to take a look at

the nuance between ['now()](/docs/reference/function/date-time/#now) and [systimestamp()](/docs/reference/function/date-time/#systimestamp) documentation. It turns out that systimestamp()(andsysdate()`) can produce

a different value on each call made during query execution. Because their output

is not stable, it can't be used when calculating boundaries of intervals to

scan.

Conclusion

The lesson learned here is that while EXPLAIN shows how a query is

executed, it does not display why this specific plan was reached. Still -

it's a very useful tool for experimenting and validating the performance model

of a query.

Remember - if you have a problem with QuestDB performance you can always join our Community Forum and ask the QuestDB team for help.